On the 'How to Science' debate

A recent letter-to-the-editor raises a familiar question: is there a singular 'Science' to defend?

There have always been schisms in science. Their visibility comes and goes. Perhaps the entry of mātauranga into consideration in Aotearoa resembles the emergence of global change issues (during 1990-2005), most notably climate change, that defied the scale and pace of 'normal' scientific activity. Here, normal was generally defined by Kuhn. It seems to me that one of our most prominent scientists has carefully warned us about these debates.

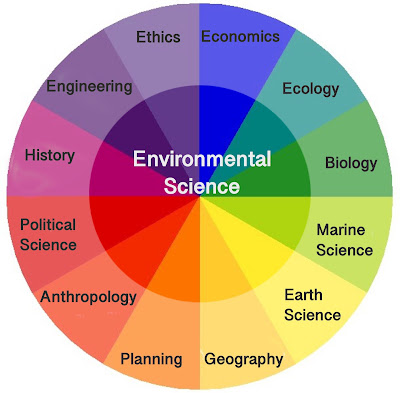

I was perhaps lucky to be educated as an earth and environmental scientist comfortable with multiple epistemologies. Yet, this luck allows me to see a painful history. There has been long-standing schism between the often dominant experimental sciences, which follow a linear or iterative method of hypothesis testing well known as 'the scientific method' versus the historical sciences, which have so artfully unwoven the history of the earth and evolution using an array of methods. The use of mathematics or models to demonstrate understanding is perhaps another practice that does not depend on falsifiable hypotheses.

I doubt I frame this debate perfectly, likely making a cartoon of one side or another. What I want to do is simply push out some material from teaching on how a similar debate played out 20 years ago. This is critical for defending the methodologies needed to address large scale environmental issues and engage with people.

Writing in Philosophy of Science, Cleland informs us (2002) (or a shorter Geology paper is good)

- There are basically two very different epistemologies operating in science – have you detected the conflicts? Here's the main link to a good short article. For a deeper, longer version see this link.

- "The reputed superiority of experimental research is based upon accounts of scientific methodology (Baconian inductivism or falsificationism) that are deeply flawed, both logically and as accounts of the actual practices of scientists."

- "Classical experimental research involves making predictions and testing them, ideally in controlled laboratory settings. In contrast, historical research involves explaining observable phenomena in terms of unobservable causes that cannot be fully replicated in a laboratory setting."

- "The most trenchant criticism of historical science, however, comes from an editor of Nature, Henry Gee, who explicitly attacked the scientific status of all hypotheses about the remote past; in his words, “they can never be tested by experiment, and so they are unscientific… No science can ever be historical.”"

Comments

Post a Comment