The Overseer Files

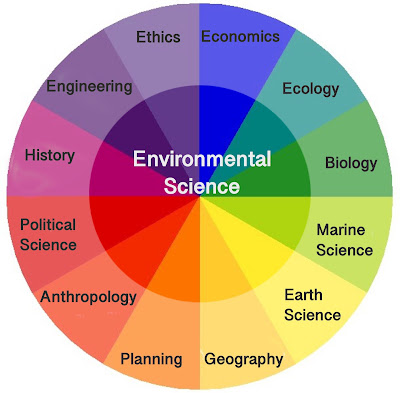

Just before we all suddenly returned to a snap lockdown, and excellent use of scientific models to manage New Zealand COVID response, we were wading through a much less rosy review of one of Aotearoa's most important scientific models - used for farm nutrient management and water quality regulation. I had prepared some comments at the Science Media Centre's (SMC) request for Expert Reaction as an Environmental Scientist and as President of the NZ Association of Scientists. Neither they nor science correspondents in the media have time for a deep dive into the topic at the moment so I'm filing my comments here for discussion.

An MPI-commissioned peer review report has concluded that key aspects of the Overseer model used for water quality regulation are not fit for purpose. The Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment (PCE) has described the report as “devastating”, while those responsible for the model defend it to users.

|

The contrast confirms an undesirable situation I’ve previously framed by saying “Overseer is the best model we have, because it is the only model we have.” The problem evolves from a paradox those who develop scientific models have been aware of. Models that are heavily used can be very difficult to improve and modify as needs change. A model’s usability can be its own enemy when it comes to incorporating detailed science. And it is important to note that the review didn’t examine the usability and value of the Overseer user interface, and farm data collection.

Those looking at the situation outlined by the peer review panel’s report on the Overseer model last week, will be wondering how such an array of problems and challenges can arise. Overseer has become essential to New Zealand’s water quality regulation with an emphasis on regions and catchments where nitrate problems exist. Overseer was designed for these environments: well drained soils over aquifers. By becoming a one-size fits all model supporting regulation, the Overseer model has captured focus for the entire country, including areas and situations the review finds are outside its core strengths and stated purpose.

The review points to the symptoms of problems that must at least in part be addressed through considering how New Zealand invests in science and models, assigns ownership, oversight and confidentiality, and connects the model product to policy as well as its original purpose – farm nutrient management. Adjustments have been made to Overseer's ownership and business drivers, including becoming a non-profit, but the adjustments do not fully address the openness and ownership issues raised in 2018 by the PCE. It has to be pointed out that the scientists and executive leadership in the Overseer team could be making the best incremental improvements and decisions they can, and not have the resources or room to make changes that could have resulted in a more positive review. Nevertheless, as someone working to make measurements and models point in the right direction for both farmers and freshwaterwater, the review explains a number of problems that shouldn’t have been allowed to evolve and must be solved. Below, I examine the findings in more detail, as well as where this can lead.

What is the Overseer model? It has evolved over more than 30 years to represent understanding of the relationship between nutrients and production on farms. For water quality, its key feature is nutrient loss from the root zone, originally developed to describe nitrate leaching from the root zone well-drained soils. It is also important to understand that Overseer results are often used as a catchment total, but Overseer is not a catchment model. It only models only the root zone of productive land areas.

The recently released review makes it clear that the Overseer model has represented a series of developments that may have been somewhat defensible on an incremental basis to represent a growing array of challenges addressed on limited funding. The model is used to regulate losses of nutrients to water, but wasn’t originally aimed at this purpose. Despite some new versions, the model’s structure lacks the principles and approach expected for scientific system modelling to be seen as excellent for supporting water quality regulation.

The key problems described by the reviewers include incremental solutions developed into components that overlap, and appear likely to yield conflicting or confusing results. Among the key issues, the model appears to have overlapping modules that don’t consistently balance the mass of water or nutrient elements moving through the plant-soil-animal system. As a result, the review found Overseer is problematic to use as a component of catchment modelling, particularly outside the well-drained soils for which it was mainly designed. Catchments that include imperfect and poor drainage dominate our national area, while Overseer’s focus on well drained soils suits mainly the Central Plateau and Canterbury plains. Overseer is also centered on an unusual nitrate-only approach, apparently lacking realistic tracking of other nitrogen species which are important in many regions, and may also be problematic for phosphorus, also raising questions about extensions to estimate pathogens and greenhouse gas budgets.

The Government response appears appropriate, but the magnitude and urgency of the problem is worrisome. As I pointed out three years ago and others have highlighted recently, a failure to identify and implement a principles-based approach explained the contamination of Havelock North’s drinking water. In that case, bespoke rules and decisions were faulted and remind me of the findings of Overseer Review. In contrast, building on a series of principles tends to lead to success, and also supports a range of modelling and measurement approaches to achieve these, including competing solutions. In the absence of principles, there can be both confusion and a desire to avoid developing alternative models because they are seen as duplicative.

Helpfully, an updated set of international principles for nitrogen management has just become available this month (UNCECE, p21). Internationally accepted principles and recommendations may be particularly important if they begin to be considered in market access or in the value of exported produce.

The central principles include using input-output balance modelling, and recognising that properly controlling nitrogen inputs influences all nitrogen loss pathways: what goes in must come out. The 5th principal is specifically framed, "These are attractive measures because reductions in N input (for example, by avoidance of excess fertiliser, of excess protein in animal diets, and of human foods with a high nitrogen footprint), lead to less nitrogen flow throughout the soil-feed-food system.”

These key principles make reducing nitrogen excess in animal diets particularly clear as an opportunity that can maintain production, and note it is a challenge for grass-fed agriculture in particular (expanded in UNECE, p81-84). The Overseer review highlights that the model appears to be relatively insensitive to excess nitrogen animals eat, which is then concentrated in urine, leading to multiple losses including nitrate and the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide. This implies more can be done than previously estimated to optimise animal diets: previous modelling could have missed ways to improve or maintain productivity and profitability while reducing the impacts of nitrogen losses to the environment. That’s an example of a major opportunity where good science in a good model can help farmers innovate toward lower environmental impacts, and keep improving the environmental image of New Zealand agriculture.

The principles also support the use of a single integrated approach, for productivity, greenhouse gases, and nitrogen losses to the environment, with farm-scale decision-making as a key focus. A positive aspect of Overseer is that it has already planned to take up this challenge, with a user interface that works for collecting and managing key data for New Zealand’s main farming systems. It seemed to be on track to meet expectations to support greenhouse gas inventories for all farms within the next few years. It is potentially an integrated repository for key information that can accelerate the development of alternative scientific approaches that will prove more appropriate for particular purposes, including those signalled to be under development by MPI and MFE.

Can the “next generation Overseer" overcome the paradox that its dominant position, large user base and interface makes needed model improvements challenging? Achieving this, or other approaches that quickly reach the scale and quality needed will be difficult. Given the urgency, some may say it will be risky and duplicative to allow multiple approaches to replace Overseer. I argue the diversity of principles and spatial scales (from farms to regional and national policy), and timeframes of need establish different targets and necessitate development of some complementary and overlapping tools. We should beware of ever again placing so much weight on a single tool.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Comments

Post a Comment